On Monday night, April 22nd/15th of Nisan, Jews traditionally gather to celebrate Passover and commemorate the exodus from Egypt. We reenact the exodus through story, discussion, and song at the seder table.

CAJE's Department of Adult Learning and Growth, in partnership with our faculty, has compiled Passover insights and teachings designed to help you spiritually prepare for the holiday. We've also included links to resources that you can share around your seder tables to spark meaningful conversations.|

Freedom is Worth Everything Years ago, I read an article by Rabbi Efrem Goldberg, of BRS (Boca Raton Synagogue), which made me pause and think about the obvious: how much of Pesach – both the preparation for the holiday and the holiday itself – centers on food, on what we put (or not) in our mouths during those eight days? Now, you may say that everything Jewish focuses on food (or on the absence of it), but on Pesach this is really taken to an extreme. Keeping a kosher home on Pesach is challenging, to say the least. Who knew iodized salt cannot be used? Not to mention the different food customs which can become the source of much disagreement within families: do we eat rice and legumes (as Sephardi Jews do), or do we avoid kitniyot? Do we eat gebrochts (matza products that have touched water) or not? Do we use processed foods such as oil or do we only cook with schmaltz? Do we peel every fruit and vegetable (as is the Chabad custom) or do we not? Weeks before Pesach, we clean our homes (many times obsessively, which is not what the Rabbis envisioned), we get rid of anything that could be chametz (or sell it), we make long shopping lists, long menu lists (making sure, of course, every allergy is taken into consideration, every preference is considered, etc.) and stress over almost anything and everything related to food. We finally come to the Seder. And with all the care we had about what foods will be allowed to enter our mouths, there is one thing we seem not to be concerned about or stressed over – what comes out of our mouth. Viktor Frankl, writing about human behavior after liberation from a concentration camp, says: “The body has fewer inhibitions than the mind. It made good use of the new freedom from the first moment on. It began to eat ravenously, for hours and days, even half the night. It is amazing what quantities one can eat. And when one of the prisoners was invited out by a friendly farmer in the neighborhood, he ate and ate and then drank coffee, which loosened his tongue, and he then began to talk, often for hours. The pressure which had been on his mind for years was released at last. Hearing him talk, one got the impression that he had to talk, that his desire to speak was irresistible. I have known people who have been under heavy pressure only for a short time to have similar reactions." (Man's Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. United Kingdom, Beacon Press, 1992, p.96) You see, at the Seder, we are commemorating the liberation of the Israelites from bondage. The descendants of a people who had limited access to food (although for many of the desert years they seemed to recall a plentiful and varied buffet in Egypt…), and who were not free to speak as they wished, commemorate their freedom by eating and speaking for hours (telling their story as scripted in the Haggadah). Yet, have our mouths become too free? Have we forgotten the responsibility that comes with the ability to speak freely? Every year, after the sedarim, I hear stories of serious disagreements that happened around the Seder table: disagreements about politics; disagreements about how to observe Judaism; and so much more. I am sure this year we will add to that list disagreements over the war going on in Gaza. The freedom of speech we so hoped for as slaves, ends up being the cause of strife. So, this year, when we sit around our beautifully set Pesach tables, when we share the experience of freedom by retelling the story, let us commit to being as careful with what comes out of our mouths as we are about what goes in. Let us care for each and every person sitting around our table: the democrat uncle and the republican cousin; the more observant sibling and the less observant child; the friend who believes Israel should finish the job in Gaza in spite of civilian casualties and the neighbor who believes it should not go into heavily populated areas. Let us make a conscious decision that freedom is worth everything – and it can be celebrated with words of kindness and respect. |

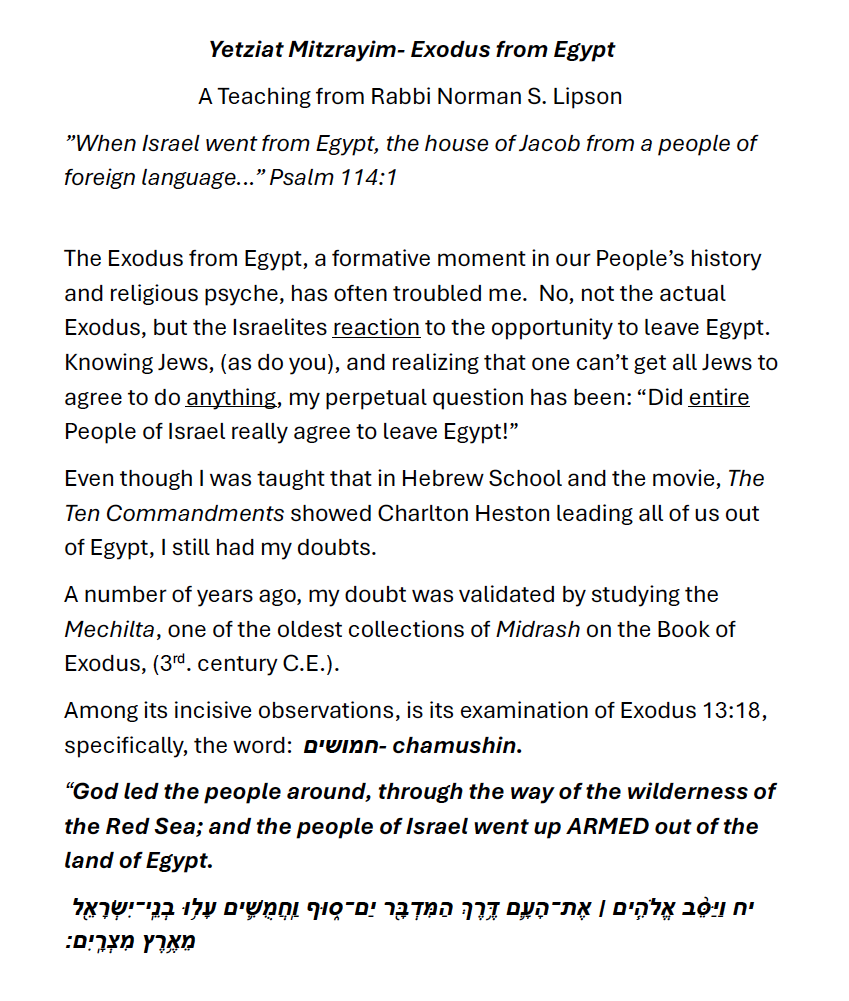

Yetziat Mitzrayim - Exodus from Egypt

A Teaching from Rabbi Norman S. Lipson

|

|

Questions:

1. Would you have stayed in Egypt with Pharaoh, “the devil you knew,” or left with Moses, for an uncertain fate and destiny?

2. How bad were the conditions for your family members in Europe for them to have left all that they knew, for the New World or Palestine/Israel?

3. What life situations might present themselves for you to leave everything in order to start a new life?

|

The Essential Elements of the 10 Plagues |

|

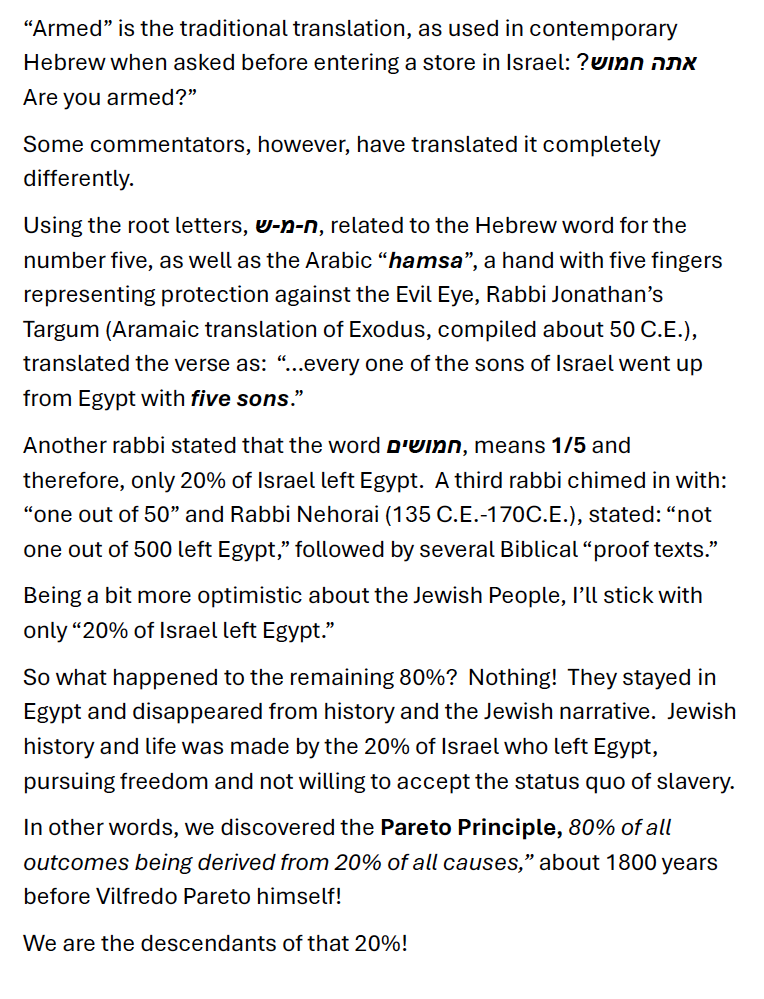

In the 16th century, famed Jewish philosopher Abarbanel discovered the essential elements of the literary structure of the plagues in the Torah. He broke them down into three segments of plagues following the pattern of when the Pharoah was warned, which begins each set of plagues and ends with no warning to the Pharoah. Pharaoh makes 3 heretical statements denying the existence of God. Each set of the plagues are intended to address the three issues:

As you go through the chart, you will find that each of the three sets gets much fiercer until the last plague rests in a category of its own. |

|

SET I (Plagues 1-3) 7:17 - In this you shall know I am God. This answers the first of the Pharaoh’s denials that God exists. Each plague focuses on all participants (Israelites and Egyptians) 8:15 Magicians recognize finger of God... therefore, He exists is what ends the set |

SET III (Plagues 7-9) 9:16 -Show you my power (in the world) The last plague, which is performed by God and not Moses, is the final definition of the existence of God. Abarbanel points out the conceptual framework of this plague.

|

|

SET II (Plagues 4-6) 8:18 - so that you will know that I get involved on earth. |

SET IV (Plague 10) Has all three messages inscribed in the verses: 11:4 - I shall go out into the midst of Egypt 7 - Providence... To differentiate and parallel the second set 8 - Power over all Egyptians |

| THE LITERARY STRUCTURE OF THE PLAGUES NARRATIVES | |||||||||

| Fore - | |||||||||

| # | Theme | Plague | warning | Time | Location | Agent of Plague | Impact Upon | Egyptian gods | |

| 1 | Introduction | Blood | yes | in the morning | "station yourself" | Aaron | Israel & Egypt | Hapi - Nile | |

| A | 2 | insecurity | Frogs | yes | no | "Go to Pharaoh | Aaron | Israel & Egypt | Heka - fertility |

| 3 | notice strangers | Lice | no | no | none | Aaron | Israel & Egypt | Geb - earth & vegetation | |

| 4 | doubt | Insects | yes | in the morning | "station yourself" | G-d | Egypt | Kehpfi - insects | |

| B | 5 | superiority | Pestilence | yes | no | "Go to Pharaoh | G-d | Egypt |

Apis/Menvis-bullgod/Hathor cow goddess |

| 6 | loss of pride | Boils | no | no | none | Moses | Egypt | Thoth-medicine, intelligence | |

| 7 | physical suffering | Hail | yes | in the morning | "station yourself" | Moses | Egypt | Nut- sky / Seth - crops | |

| C | 8 | economic | Locust | yes | no | "Go to Pharaoh | Moses | Egypt | Anubis-fields/Isis-protector against Locusts |

| 9 | chaos | Darkness | no | no | none | Moses | Egypt | Ra / Amon-Re - sun god | |

| 10 | sacrifice | Firstborn | yes | yes | none | G-d | Egypt | Pharoah's son - god king | |

| Prepared by R' Dr. Leon Weissberg [email protected] | |||||||||

|

The Deeper Meaning of the Food on the Seder Table We are all familiar with the various foods on the Seder table that punctuate the Seder. Their symbolism is also well known: shankbone - the Paschal Lamb whose blood was put on the doorposts to ward off the 10th plague; Karpas - the green vegetable to remind us of Chag HaAviv - the spring festival; the egg - to remind us of the special sacrifice offered in the Temple for Pesach; Maror - the bitter herbs to remind us of the bitterness of slavery; Charoset - to remind us of the mortar that the Israelites had to make for the bricks; salt water - the tears of slavery; matzah - the unleavened bread that we ate as we had to rush out of Egypt. But as we can imagine, it’s not really as simple as that - it never is. Many of the symbols actually have two meanings that reflect the two halves of the Haggadah and the story - from slavery to freedom. The first half of the Haggadah - before the meal - deals mainly with the story of the slavery and the second half celebrates the redemption and looks to an ultimate redemption of all humanity from slavery and oppression, which is associated with the symbol of Elijah the prophet. The breaking of the matzah at the beginning of the seder into two pieces- one to be eaten before the meal and the other as the Afikomen - the ‘dessert’ (what a lousy dessert it is - still trying to determine if we can put some chocolate spread on it) - at the end of the meal. The first piece we eat from before the meal when we are still talking about slavery, is the smaller piece. The second and bigger piece we eat is after the meal when we are celebrating redemption. The redemption is greater than the slavery! That is why Karpas is at the very beginning of the Haggadah. It is the very beginning of the story and is a reminder that in the Diaspora there was, and is, always a tendency to believe that the Jews are far more numerous and powerful than they actually are and that they are disloyal (which they never are). There is a great truth in this. In interviewing some of the pro-Hamas demonstrators, reporters found that many of them believed there were 40-50 million Jews in America!! If that was the case, our paucity in pro-sports would be even more difficult to accept! (Maybe there are 5 1/2 million). Only a society that is diligent can preserve its freedom and only a society that is willing to fight for its freedom will remain free - as the Israelites did when they sacrificed the lamb against Pharoah’s explicit orders and cast their lot with the struggle for freedom. |